Artillery modernization and support to the 2d MarDiv

The release of Force Design 2030 has precipitated significant changes in the structure of 10th Mar. The regiment maintains a two-battalion structure following the cancellation of activation plans for the 3d and 5th Battalions, resulting in adjustments to the capability and support provided to the 2d MarDiv. The divestment of cannon artillery, paralleling the larger divestment of infantry regiments and battalions, was accompanied by the establishment and consolidation of the division’s High Mobility Rocket Artillery System (HIMARS) capability within the 2d Battalion. The establishment of the Fire Support Battery consolidated the regiment’s fire support teams—long the mainstay liaison capability to its infantry counterparts—under one command while the incorporation of longer-range target acquisition systems complemented the introduction of a division organic long-range precision fires capability. Throughout this evolution, 10th Mar expanded its support to the 3d MarDiv and combatant commanders worldwide through expanded support to the Unit Deployment Program while maintaining its presence embarked aboard Camp Lejeune-based MEUs, increasing its global footprint.

These structural changes affect the regiment amid a rapidly evolving operating environment. The hard lessons of recent conflicts such as the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War and the ongoing war in Ukraine loom large as 10th Mar adapts its learning to generate forces capable of thriving amidst global crisis and contingency operations. The threats posed by adversaries’ integrated sensors and fire complexes, the increased prevalence and capability of unmanned systems on the battlefield, and the increasingly contested nature of the electromagnetic (EM) spectrum are but a few of the operational realities that drive an increased distribution of forces on the battlefield. The Service has followed suit, and the Marine Corps’ current Service-level Integrated Training Exercise and MAGTF Warfighting Exercise provide a demanding, distributed environment where 10th Mar operating concepts have been put to the test.

While 10th Mar of today may look different, its responsibilities as the Marine Corps’ Service-retained cannon and rocket artillery regiment endure. Regardless of ongoing change, 10th Mar remains postured and capable of supporting global force tasking while retaining a combat-credible capability to respond to crisis and contingency. As the regiment mans, trains, and equips in support of the 2d MarDiv, the challenges posed by contemporary threats, force structure changes, and a distributed battlefield drive defined changes in how it organizes for combat to support maneuver. It is a much more scalable and flexible artillery regiment than ever before, employing more diverse weapons systems, advanced targeting acquisition capabilities, and an improved ability to man and train capable fire support teams; 10th Mar continues to capture valuable lessons learned to optimize its support to the Follow Me Division in any capacity required.

The Arm of Decision

If it has done nothing else, the regiment’s structural changes under Force Design 2030 have shattered convention in the realm of legacy concepts of support to the 2d MarDiv. While the regiment retains two-for-two artillery battalion parity with the division’s infantry regiments, the battery-level organization of 10th Mar disrupts traditional ratios of support. The regiment’s present organization consists of seven cannon batteries and three HIMARS batteries tasked with providing support to eight infantry battalions and the additional fire support needs of the 2d Light Armored Reconnaissance Battalion while retaining a capability to support MEF-level requirements with long-range precision rocket fires or cannon artillery as needed. This problem of capacity is further strained by the reality that at any given moment upwards of 40 percent of the regiment’s firing batteries are forward deployed—or preparing to deploy—in support of global force tasking.

These structural changes and their impact on conventional methods of support exist in the context of a broader landscape of operational challenges stemming from both contemporary adversaries and the operating environment. They do not, however, change the foundational demand placed on the regiment. As 10th Mar continues to fulfill its mandate to effectively organize for combat in fulfillment of its fire support tasks, it is much more than simply an artillery regiment in support of a division.1 The regiment has evolved into an exceedingly flexible organization, provisioning scalable fire support from the regimental to cannon and rocket platoon levels, supported by a tailored approach to tactical mission assignment at all echelons informed by the threat, force structure, and the distributed nature of the battlefield.

Legacy Ratios of Support and Habitual Relationships

Traditionally, the direct support tactical mission has been the hallmark of the artillery battalion, with “minimum adequate support” considered to be one artillery battalion for every infantry regiment.2 This paradigm implied that one infantry battalion required one cannon artillery battery (or six howitzers). The regiment’s artillery battalions are no longer optimized to maintain direct support relationships with infantry regiments, a reality driven as much by its reduced quantity of cannon artillery as by the non-uniform structure of its battalions. (Five cannon batteries are organized under the 1st Battalion while all HIMARS batteries are retained under the 2d Battalion.)

In addition to the inability to maintain legacy ratios of support to maneuver units, the bifurcation of the traditional liaison capability retained within 1st and 2d Battalions to the regiment’s new fire support battery redefined the traditional approach to fire support coordinator (FSC) responsibilities in support of infantry regiments. The regiment’s loss of battery to infantry battalion parity did not extend to its fire support teams, and regimental fire support team officers in charge have subsumed the roles of regimental FSC from the artillery battalion commanders, taking the “habitual” relationships of yesterday with them. This has its own advantages, as this field grade officer, rather than splitting responsibilities between that of an artillery battalion commander and FSC, is completely focused on the planning and employment of fires and effects, coordination and deconfliction of fires, and the disposition of the platoon’s fire support teams. In the performance of these duties, the regimental FSC is fully integrated into the infantry regimental commander’s staff and in the best position to have an impact on fire-related decisions. This splitting of responsibilities has made the provision of fire support to maneuver units a more collaborative process, and the artillery battalion commander remains an invaluable stakeholder in providing support to maneuver units in cooperation and collaboration with the FSC. This collaborative relationship has been exercised and refined during Service-level exercises, doing much to optimize artillery tactical missions and organization for combat in support of the maneuver commander’s concept of fires.

Tailorable Employment and Tactical Missions at all Echelons

The regiment’s solution to bridging the gap posed by contemporary threats, evolving force structure, and the challenges posed by the distributed battlefield has been one of a flexible approach to tactical mission assignment at all echelons. While the distribution of firing platoons and batteries across the battlespace is a necessary step to improve survivability in the face of emerging and evolving threats, it is also driven by the regiment’s requirement to meet its fire support tasks in support of maneuver forces operating at greater distances. Platoon-level operations for cannon and rocket artillery are often necessary to ensure that zones of fire maintain their ability to support zones of action in a distributed environment, a reality that has reciprocal effects on tactical missions at the battalion level.

The distribution of a reduced quantity of cannon artillery systems increasingly makes general support the tactical mission of choice at the battalion level, wherein the battalion is required to support the force as a whole while remaining prepared to support subordinate elements therein.3 An artillery battalion assigned the general support tactical mission while employing distributed firing platoons is thus better able to measure its tempo of support to maneuver, ensuring that it meets essential fire support tasks for the force while retaining dedicated firing capability to respond to immediate requests by forces in contact at subordinate echelons.

An increased proficiency in distributed operations also means that tactical missions are relevant and viable at the battery and platoon levels, providing 10th Mar with a flexible means through which to tailor support to individual formations, maintaining the ability to weigh more responsive fire support to specific maneuver units if required. This is especially relevant for the regiment’s increased quantity of long-range precision fires. HIMARS batteries, organized in three platoons of two launchers each, are exceptionally flexible firing agencies that can be task-organized to provide tailored and responsive fires to multiple echelons of command through the deliberate application of tactical missions to the battery and platoon levels. Their effectiveness is bolstered as well by structural changes that have introduced dedicated billets for fires plans officers at the artillery battalion, supporting battery-assigned liaison officers with interfacing and integrating effective precision fire support with higher echelons of command.

Impacts to Effects of Fires

While the scalable and flexible employment of firing units at every echelon helps compensate for shortcomings in traditional ratios of support, the regiment’s reduced capacity of cannon artillery does force a reappraisal of the traditional effects of fires provided by the division’s organic artillery. Without the capacity to sustain traditional direct support relationships, batteries and battalions are challenged to provide ammunition-intensive suppressive effects to individual infantry formations while at the same time retaining sufficient capability to support units across the breadth of the GCE.

Fielding a reduced structure of cannon artillery against ever more capable adversaries, the regiment’s ability to provide suppressive fires is increasingly unsustainable in favor of a more optimized approach to destruction and neutralization fires, enabled by the regiment’s HIMARS capability and its ability to achieve precise effects at range. While this allows the regiment to retain its ability to degrade or render key adversary capabilities incapable of accomplishing their missions, it also increases the requirement for the supported unit’s targeting processes to employ the finite, yet lethal, resources at their disposal most efficiently. Supported units are not alone in meeting these requirements, being reinforced by the weight of the regiment’s fire support battery.

Fire Support Battery

As structural reorganization within the Regiment’s firing battalions has disrupted historical habitual relationships with 2d MarDiv’s infantry regiments, a new unity of effort has emerged with the establishment of the Fire Support Battery, 10th Mar. Active since October 2022, the 10th Mar was the first artillery regiment to establish a fire support battery by Force Design artillery modernization efforts. The transfer and consolidation of 1st and 2d Battalion’s fire support platoons, further supported by the integration of the 2d MarDiv Fire Support Coordination Center, created a singular unit that is structured to source habitually aligned fire support teams to the division’s infantry regiments, their battalions, and 2d Light Armored Reconnaissance Battalion. For the first time, a unified headquarters platoon and command element exists to support efforts to man, train, and equip fire support teams for combat operations in support of scalable fire support solutions for maneuver formations. The result is better-trained fire support teams for global force tasking, crisis response, and contingency operations.

The cascading effects of the fire support battery’s establishment extend well beyond the consolidation of dedicated support to maneuver. The consolidation of the division’s fires and effects integration expertise continues to support the development and refinement of high-quality, standardized fire support team training and evaluation packages—overseen and executed by the battery’s training and headquarters sections—to provide a uniform capability to the regiment’s supported units. The consolidation of the regiment’s tactical air control party program has also improved its ability to generate and train quality joint terminal attack controllers and joint fires observers for the division. This has correspondingly increased the battery’s ability to harness its manpower and equipment resources to better task organize scalable fire support teams for emergent crisis response requirements and taskings, providing a tailorable capability when required.

This new structure is not without its growing pains, and the establishment of the fire support battery did not singularly eliminate the regiment’s challenges in the areas of unit lifecycle management and equipment. Fire support teams, while better trained under the present fire support battery organization, remain affected by occupational-specialty shortages.4 Because of these issues, the fire support team force generation often struggles to keep pace with the pre-deployment training cycles of overlapping global force management requirements. Similarly, an enduring need exists to continue to modernize communications and optics equipment toward systems that are lighter, less power-consuming, and better optimized for the joint environment. The fire support battery is better postured than ever to address these challenges, and the resulting consolidation of expertise within the regiment has brought about a new unity of purpose in the liaison capability 10th Mar provides the division.

Target Acquisition Advances

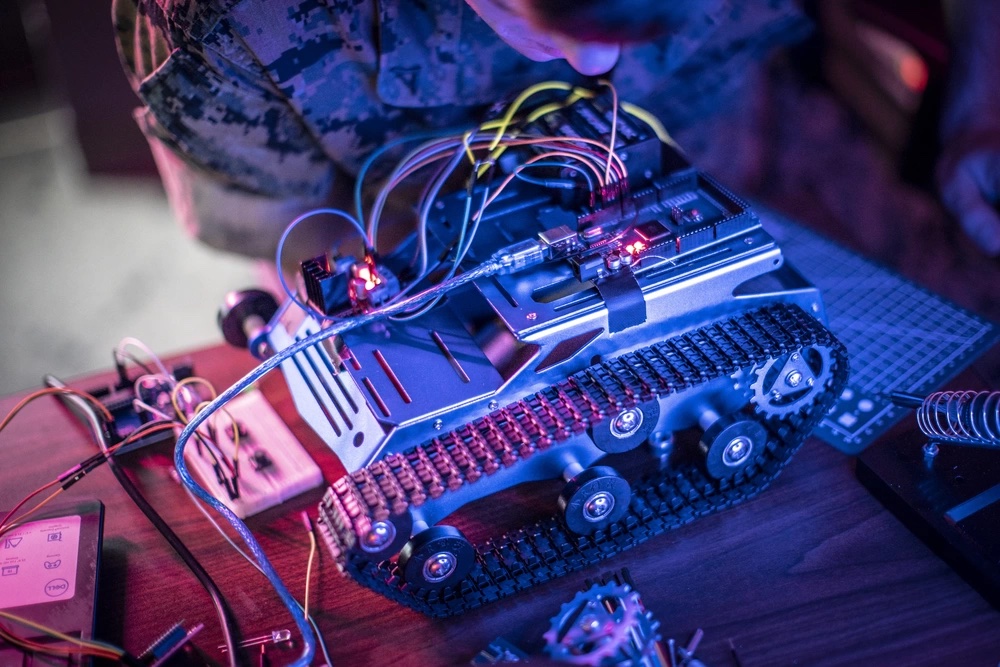

As the establishment of the fire support battery sustains and advances 10th Mar’s habitual liaison capability to supported units, the regiment’s organic target acquisition capability has equally benefitted from new technology and employment concepts in support of the division. The 10th Mar Target Acquisition Platoon is at the leading edge of modernization efforts in cooperation with Combat Development and Integration and Marine Corps Systems Command to field and test new equipment. The Regiment’s Block 2 AN/TPS-80 Ground Air Task Oriented Radar (G/ATOR), a ground weapons locating variant optimized to acquire and track hostile indirect fire, and Scalable Passive Acoustic Reporting and Targeting Node (SPARTN) are together more potent than their predecessors.5 This advanced equipment is paired with the benefits that come from structure growth, and a benefit of the 12th Mar’s transition to the 12th Marine Littoral Regiment is the subsequent inheritance of counter-battery radar teams divested from the 3d MarDiv. These structural gains will further increase the regiment’s sensor capacity by two G/ATOR and two Lightweight Counter Mortar Radar systems—welcome additions to 10th Mar as they further contribute to shortening kill-chains and enhance support to 2d MarDiv and II MEF’s counterfire needs.

As of January 2024, the regiment has completed fielding half of its allotted G/ATOR systems and is already benefitting from this exceptionally capable system which drastically outperforms legacy AN/TPQ-46 Fire-Finder radar systems in its combat capability, allowing the regiment’s counterfire capability to keep pace with its evolving organization for combat. The radar’s extended range has opened opportunities for new and creative employment concepts for the target processing center’s liaison capability between radars and firing agencies. Increased target processing center’s employment at the MEF and division fire support coordination center levels improves target acquisition and proactive counterfire capabilities at these echelons while better familiarizing them with counter-battery capabilities.6 This will bridge the maneuver’s counterfire acquisition and delivery capability at the extended ranges of an increasingly distributed battlefield.

This year also introduced another much-needed upgrade to the regiment’s target acquisition suite with the introduction of the SPARTN system. A passive acoustic sensor whose primary function is to report acoustic events, the SPARTN provides an improved capability to cue G/ATOR emissions on detections that meet unmasking criteria. This complementary relationship between the SPARTN and G/ATOR increases system survivability and provides a more resilient counterfire capability to the 2d MarDiv. The SPARTN’s significant reduction in size, increased communications capability, and longer battery lifespan is directly aligned with supporting effective coverage in support of any level of sustained, distributed operations. Together, these advances represent the regiment’s contribution towards ensuring that counterfire remains the shield that allows the 2d MarDiv to wield its sword of supremacy in any crisis or contingency operation.

Future Change and Opportunities for Optimization

While the 10th Mar remains postured to support the requirements of the 2d MarDiv, the regiment’s organization will not remain static in its march toward the future operating environment. The regiment’s current operating concepts and organization for combat yield continual lessons on areas for investment germane to effective fire support employment both now and into the future while future structural changes will continue to adjust its organization and support to the division.

Areas for Further Optimization

The regiment’s reduced density of cannon artillery formations and the corresponding emphasis on destruction and neutralization fires requires greater investment and prioritization in employment techniques for dual-purpose improved conventional munitions, rocket-assisted, and family of scatterable mine projectiles over traditional high explosive variable-time combinations. While these presently available munition types can assist in offsetting the prohibitive expenditure rates required to achieve firepower and mobility kills on armored equipment, long-term investment in the capabilities of cannon artillery must emphasize greater infantry access to longer-range cannon fires to support their mission-essential tasks and complement the expanding range of sensing capabilities at every echelon.

As the ongoing conflict in Ukraine illuminates, cannon mobility also requires further investment. The conflict has in many cases highlighted the disadvantage that towed artillery formations encounter in a high counter-battery threat environment, where the ability to reposition on short notice equals advantage and often survival.7 The Marine Corps’ current Medium Tactical Vehicle Replacement is not optimized for keeping pace with increased infantry mobility, nor the requisite displacement times to avoid contemporary counterfire threats. The age and usage rates of the Medium Tactical Vehicle Replacement have also affected ongoing operations, as availability rates have decreased upwards of 60 percent in the past decade.8 In light of these realities, alternative prime mover options incorporating a lower tongue weight and smaller chassis merit increased consideration, while voices advocating for the Marine Corps to more seriously explore adopting a self-propelled cannon artillery system deserve additional attention.

While the batteries and platoons of 10th Mar continue to demonstrate an increased proficiency at distributed operations, cannon, and HIMARS batteries must continue perfecting these techniques while equipped with the requisite communications equipment to support dispersion at the cannon section and rocket launcher level to maintain uninterrupted command and control. Legacy communications equipment employed across traditional wavelengths does not adequately meet this aim. Very high-frequency systems, employed in a nearly exclusively omnidirectional pattern, increasingly make firing units vulnerable to rapid detection and targeting. Similarly, time-intensive techniques for the effective employment of high-frequency communications are regularly outpaced and outclassed by the effective usage of new wideband communications technologies; these systems are not currently available in quantities sufficient to support an increased number of independent and distributed firing formations throughout a non-contiguous battlefield. Ongoing exercise participation at the Service-level has validated the benefits of wideband satellite communications systems over legacy waveforms, and the capability merits serious consideration for future investment across the Marine Corps’ artillery formations.

Change on the Horizon

The regiment’s contemporary lessons learned and operating concepts are in many ways a foundation for its future force structure and roles within the division. Current fire support systems and liaison capabilities to supported units are only a waypoint towards the complete structure changes outlined in Force Design concepts.

Endorsed by the 2023 Artillery Operational Advisory Group and currently underway in conjunction with Combat Development and Integration, the positive changes from the establishment of the fire support battery may one day see the organization grow to a battalion-level command. This fire support battalion would provide its commander the authority required to compete for resources in the form of personnel, money, and equipment within the regiment. Presently, the fire support battery rates 342 Marines and sailors as part of the table of organization, and while on-hand numbers are smaller, they will only continue to grow based on Headquarters Marine Corps manpower projections. The command element and staff appropriate to manage this large organization would greatly enhance the future battalion’s ability to functionally manage a formation that serves a division headquarters, two regiments, eight infantry battalions, a light armored reconnaissance battalion, and myriad emergent requirements and requests that demand fire support expertise. A future fire support battalion will improve the regiment’s ability to meet 2d MarDiv’s demand for adaptable and relevant fire support teams.

The regiment’s current cannon and rocket artillery structure will further change with the fielding of the Navy-Marine Corps Expeditionary Ship Interdiction System (NMESIS) in the coming years. 10th Mar has remained keenly invested in Service-modernization initiatives through involvement in NMESIS development and extended user evaluation to best forecast impacts to future organization and operations. 10th Mar anticipates transition of initial batteries to NMESIS as early as fiscal year 2026 and maintains the planning horizon required to ensure initial units identified to receive training are prepared to develop best practices and recommendations for system employment.

The introduction of NMESIS to the 10th Mar will see the regiment go through a subsequent reduction of cannon artillery batteries, placing a greater onus on the efficient employment of the division’s organic cannon artillery capability in support of recurring and emergent operations. The introduction of a naval interdiction capability within the 2d MarDiv will no doubt have a marked impact on the proficiencies and capabilities demanded of 10th Mar. Facing these changes, the regiment’s ongoing success in furthering the efficient and flexible employment of distributed firing agencies, integrating long-range precision fires systems and employment techniques within the division, and improving its liaison capability and target acquisition complexes are laying the foundation upon which 10th Mar’s future capability will stand. While missions and fire support systems will change, the adaptability and foresight that has long been the hallmark of Marine Corps artillery professionals will continue to ensure the regiment remains best postured to support 2d MarDiv now and into the future.

Conclusion

As its structure and concepts of employment continue to evolve, 10th Mar stands as one of the most flexible formations within 2d MarDiv. The regiment continues to meet the challenges of contemporary threats, the implications of ongoing force structure changes, and the challenges of an increasingly distributed battlefield with an approach to innovation that has redefined its organization for combat and allowed it to keep pace with its enduring responsibility to provide timely and accurate fires in support of the Follow Me Division. 10th Mar remains postured to sustain its support to global force tasking while maintaining scalable cannon and rocket artillery formations ready to respond to crisis or contingency requirements.

The regiment’s current successes do not overshadow areas where it can benefit from continued investment and optimization. Increased investment in the mobility of the Marine Corps’ cannon artillery will go far in enabling the survivability requisite for the modern battlefield, a demand reinforced by the 10th Mar’s reduced capacity of cannon systems and reevaluation of the effects they provide. Similarly, Service-level solutions to manpower constraints will help ensure that firing batteries and fire support teams can continue to man, train, and equip at a level of parity with maneuver formations now and into the future.

While structural changes have, in many ways, shattered convention in the areas of legacy ratios of support to maneuver units and traditional approaches to tactical missions, the result is a more dynamic artillery regiment that is better postured to maintain effective support to the division. This is no small accomplishment, and great credit is due to the Marines and sailors whose daily efforts ensure that the 10th Mar remains 2d MarDiv’s Arm of Decision.

Notes

1. The four fire support tasks are supporting forces in contact, supporting the commander’s concept of operations, integrating fire support with the scheme of maneuver, and sustaining fire support. Headquarters Marine Corps, MCTP 3-10F, Fire Support Coordination in the Ground Combat Element, (Washington, DC: 2018).

2. Current doctrine acknowledges the battalion as the echelon “normally” assigned a tactical mission. Headquarters Marine Corps, MCTP 3-10E, Artillery Operations, (Washington, DC: 2018).

3. Ibid.

4. Field artillery officer, fires and effects integrator, and joint terminal attack controller respectively.

5. The regiment fields the Block 2 G/ATOR system. The Block 1 G/ATOR system provides the Marine Corps with an air-defense and surveillance radar capability.

6. “Proactive counterfire” is a vital component of mid- to high-intensity conflicts to limit or damage hostile fire support systems and is incumbent on allocating proportionate target acquisition assets, normally at the MEF and division levels. For more information, see MCTP 3-10F, Fire Support Coordination in the Ground Combat Element.

7. Sam Cranny-Evans, “The Role of Artillery in a War Between Russia and Ukraine,” Royal United Services Institute, February 14, 2022, https://rusoi.org.

8. Availability rates based on data maintained through Global Combat Support System-Marine Corps R12, analyzed by 1/10 Mar from 2012 through 2024.